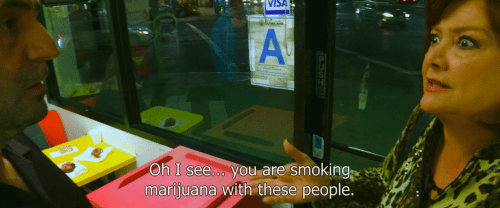

Tangerine is a 2015 American independent film directed by Sean Baker and starring Kitana Kiki Rodriguez and Mya Taylor as Sin-Dee and Alexandra respectively; two transgender sex workers searching Los Angeles for Sin-Dee’s cheating pimp boyfriend on Christmas Eve. The casting and directing of this film is especially significant, however, in the particularity of explaining some of the critical responses to the film. While Mr. Sean Baker identities as a cisgender straight white male, the two actresses playing the lead characters are transgender, making Tangerine, a low budget dramedy filmed (to a wonderfully saturated effect) on an iPhone 5, somewhat of a landmark moment for trans history and trans lives documented in narrative cinema. It is the first time where transgender people are quite visibly playing trans characters and this fact is taken not as fodder for some sort of perverted, transphobic comedy but as a fact of these characters’ existences. It is quite significant to have characters such as these who’s stories have been so underrepresented for so long to be presented as the main characters within a Hollywood narrative exercising agency over their own womanhoods. However, it is these trappings and narrative bones on which the film builds itself and it’s concerns that have been critiqued by some and thus begs the question: where does Tangerine actually fall between the lines of empowerment and exploitation?

In a 2015 article by Rich Juzwiak, it is made evident to the reader rather quickly that the film Tangerine drew an overwhelming amount of critical praise from the mainstream art and critical communities. This is true. The film was lauded upon it’s release and was subsequently nominated for numerous independent film awards, most frequently highlighting the film’s directing, writing, and acting. Juzwiak is critical of the makeup of the creative team. The author raises the point that since the film was written and directed by Baker and another cis, white, straight man, that it is impossible that it would be able to accurately portray the experiences of trans women. The article accuses the film of transphobia as evidenced by it’s portrayals of “angry black women” and trans women relegated to existing within the role of a sex worker or a sexualized and/or violent role. Particularly highlighted is Sin-Dee’s character arc with another woman named Dinah, as she is shown dragging the latter through town and abusing her for sleeping with her boyfriend. To this point, I feel that the film actually is much more progressive than this reviewer seems to think as it includes the experience of not only one black woman but many. Not only one trans woman appears in the film but multiple and not all of them purport to perform sex work. I do not find the film to be exploitative in terms of the subject matter it includes and presents. As agreed upon by another 2015 article by Morgan Collado, the film’s handling of the sensitive subject matter or sex work and poverty in LA is very realistic and important. To view the film as a reduction of the trans experience for a straight audience would be a fallacy. As the Collado article points out, Sin-Dee’s dominate and power exercised over Dinah disallows her from invalidating Sin-Dee’s womanhood. In Tangerine, it is often the trans women who are presented as having power. This issue of “presentation and representation” is further considered in Collado’s article as they examine how the film yields and exercises real-life transphobia, transmisogyny, and trans experience.

While Collado ultimately praises much of the film and particularly the agency the film gives to it’s trans characters, the author is critical of the character of Razmik. Razmik represents the “B” plot essentially. He is a taxi driver who, when he is not at home with his wife, daughter, and mother-in-law, has an attraction or fetish for transgender streetwalkers such as Sin-Dee and Alexandra. At the end of the film, Razmik is ultimately caught in this act by both his wife and mother-in-law and is shamed in a sense for his desire. He is “othered” by his own community just as Alexandra and Sin-Dee have been. This, however, is a criticized display of the draping of transmisogyny across a character that only uses trans characters for pleasure. In Collado’s view, Razmik is just as negative a figure as Chester, Sin-Dee’s cheating pimp boyfriend, as he has no respect for anyone or any woman in the film beyond his need for pleasure from these said women. He is not an ally or an other, but simply a user and a exploiter.

Tangerine is and actually remains to be one of my favorite movies. Not only because of the aesthetic experience of LA that it presents, but because of the unique lives and stories of its characters. Hopefully, as film continues to grow in it’s representation, perhaps people like Sin-Dee and Alexandra won’t seem as novel to us after all.

Citation:

Collado, Morgan, et al. “A Trans Woman of Color Responds to the Trauma of ‘Tangerine.’” Autostraddle, 27 July 2016, www.autostraddle.com/a-trans-woman-of-color-responds-to-the-trauma-of-tangerine-301607/.

Juzwiak, Rich. “Trans Sex Work Comedy Tangerine Is the Most Overrated Movie of the Year.” Gawker, defamer.gawker.com/trans-sex-work-comedy-tangerine-is-the-most-overrated-m-1717662910.

Love what you’re saying about the power dynamics in the film. In the world of Tangerine everyone is disenfranchised, that is the part of the world that Sean Baker is pointing his camera at. But within the film it is so clear that the trans characters are dominating the world around them. We find out that their power is hollow for dramatic effect, but I think that only serves to highlight the emotional truth in the film, while still letting us have fun with the story

LikeLiked by 1 person

I appreciated your comment on how this movie really shined a light on the transgender community for who they truly are and not as some comedic joke. You mentioned Juzwiak’s article that stated how Tangerine had to be transphobic for its portrayal of “angry black women.” You also stated that you disagree with the argument and you thought the film was way more progressive than the average viewer believes. I agree with this, not because of your claim that there were many trans women involved in the film and not all of them represent sex workers. I think its much deeper than that. This movie is progressive because it presents the harsh reality of our world. This is life of many people. Especially ones that must deal with the many obstacles that intersectionality brings to the table. I loved much of Collado’s article. I agree on a spiritual level that to hide or shame sex work and poverty in LA is not just a fallacy but quite ignorant as well. Sheltering the viewers from the truth does nothing but applaud transphobia. The part of the article in which Callado and I disagree, is on her views of Razmik. I do not see Razmik as a “user” or “exploiter”. He is just a human caught up in the lusts and pleasures of life. I don’t not believe he disrespected any of the transgender characters within the movie. I don’t even believe he disrespected his wife because of their “agreement” that they are seen to have. Anything he wants or lusts for is his business, we should not judge him for it.

LikeLiked by 1 person