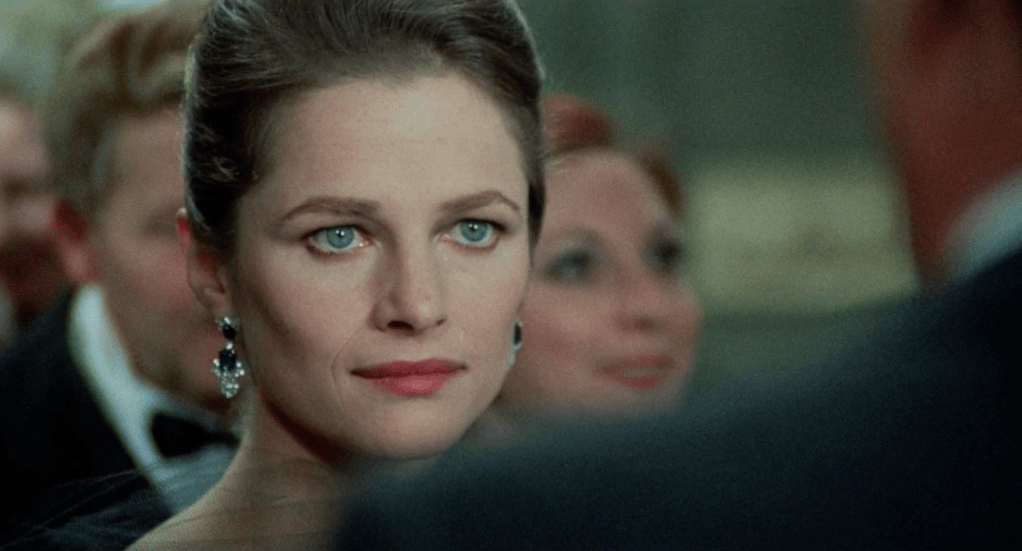

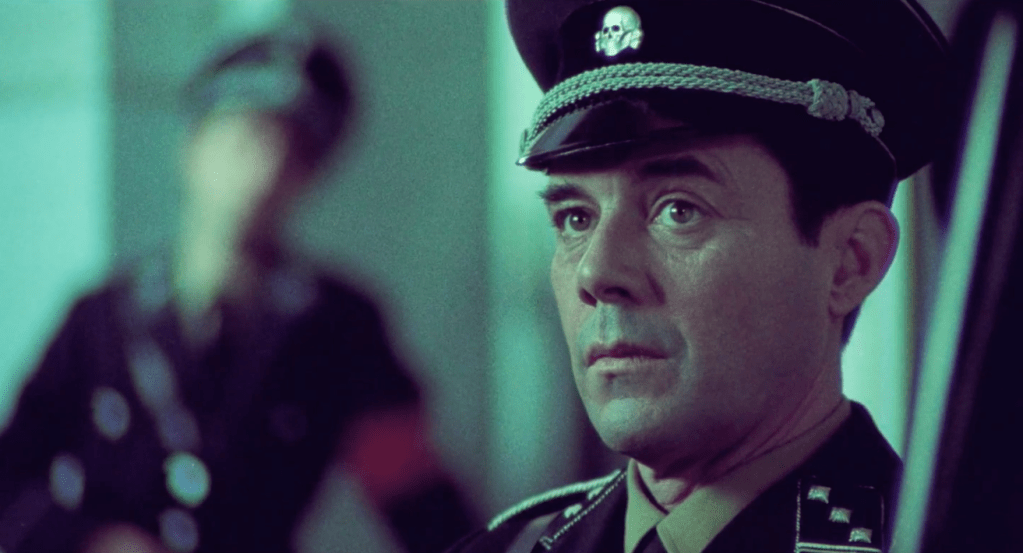

Released in 1974, The Night Porter is an English-language erotic drama by the Italian director Liliana Cavani, and starring the British actors Dirk Bogarde & Charlotte Rampling. Bogarde plays a lonely night porter, Max, living and working at a hotel in Vienna in the late 1950s. Everything seems rather unremarkable about the day Max is having minutes into the film when he makes a chance & totally fatalistic encounter with a young woman by the name of Lucia, played by Rampling, who happens to be staying with her husband in the hotel where Max is now working. Doomed from the moment they lay eyes upon each other again, it is this moment that the film reveals the past relationship between these two characters and thus the fascistic bond they share by way of cutting to and from a series of flashbacks. In these flashes of images of prisoners in telltale striped pajama-reminiscent garb surrounded by SS. Nazi officers in perfect regalia, the film comes into focus and locks into gear.

Suddenly, Lucia is pictured amidst the disparate faces, with shorter hair and dressed in a pink dress with matching bow, suggesting a much younger girl than the refined and suddenly petrified woman introduced moments prior. In the next seconds, Max is seen no longer in his three-piece suit but in a pitch black SS. officer uniform complete with a whirring film camera. And then, the point of no return for the film’s audience as the camera appearing in Max’s hands is suddenly facing the viewer with it’s lens. The viewer is all at once implicated and entrapped by the history of Max & Lucia’s intrigue and depravity filled relationship just as they have been and remain to be all over again. Liliana Cavani, the filmmaker behind the camera, is deliberate with this sequence as it reveals the very subject of the film itself: the complicity on both the individual level as well as the imagistic, filmic, and representative levels with the codes and transgressions of the specially fascistic past in question. It is in this complicity that the film finds it’s double life: both the imagery within the flashbacks and imagery of real time within the film occupy the same space and hold the same weight. The past is present which is fated by the concurrent past.

Interestingly enough however, The Night Porter stands as an extremely controversial film that many have deemed to exploitative and even pornographic in and of itself. Premiering only a year before 1975’s infamous and actually pornographic American film Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS is released, The Night Porter received rather mixed and frequently damning reviews on it’s initial run, especially within the American press and criticism circles. With titles of perverse and most of all exploitative, the responses beg the question: is the film exploitative? It is upon this question that the film walks a delicate line and in fact, one of the very purposes of the film’s existence as a piece of media is to commentate on this very idea exploitation and moral questions of the representation of fascism within a filmic mode.

In their book, The Unmaking of Fascist Aesthetics, author Kriss Ravetto defines fascism in multiple ways. In particular, they choose to highlight the historical idea that fascism and more specifically Nazism, apart from being responsible for some of the most horrific atrocities the world has even witnessed, lack any greater or truer ideology or course of action beyond the guise of an intense sense of nationalism masking ethnic cleansing. Ravetto bolsters Walter Benjamin’s idea the the politics of fascism was simply the “aestheticization of politics” or politics as merely aesthetic in order to reach the desired end of control by means of domination and violence. In addition to this point, Ravetto also brings up Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe’s theory on nazism as not at all a legitimate or sensible political system, ideology, or party but rather, “the rhetorical performance of myth” or “a myth of a myth”. Despite this performative and theatrical presentation that was often attached to examples of fascism, the actions Hitler & Mussolini’s regimes enacted cannot be forgiven and cannot and have not been erased by time. Despite the surface-level rejection of fascism in a post-war era, fascistic ideals still appear in spades in capitalist and bureaucratic dealings. Ravetto themselves ultimately in their research come up against, “the impossibility of disengaging visual and rhetorical constructions from political, ideological, and moral codes.” Aesthetics or even the representation of said aesthetic cannot be separated from ideology and action, no matter the politics involved but especially when it concerns fascism and the lasting impact of the actions that the political ideology has left behind for an eternity.

In consideration of the film’s understanding and portrayal of fascism of an ever-infectious and structured desire that still permeates into the present moment from years & years in the past as well as the filmmaker and actor’s documentarian and military involvement in the Third Reich’s emancipated concentration and death camps at the end of World War II, The Night Porter lacks the motive of exploitation. After studying as the only women in her film school, Liliana Cavani would travel all over her home country of Italy as well as all across Europe gathering enormous amounts of documentary footage for documentary assignments she had been sent on. This time and constant filming resulted in Cavani’s two first formal documentary projects. They included: History of the Third Reich (1961–62) and Women of the Resistance (1965). Both of these documentaries focus on illuminating the atrocities and war crimes against humanity that went on inside of the camps, the second one specifically focusing on women prisoners of war who survived that camp and were able to to tell their story. With this experience, not only did Cavani retain an exponential amount of information about the actions of the Third Reich, but she was actually able to understand these concepts from the actual people who experienced them as well as with the sensibility of an honest documentarian. In terms of the actors’ experience with WWII and its aftermath, Dirk Bogarde was actually enlisted as a British soldier and was deployed and did fight in the war. He actually had experiences as some of the first Allied soldiers to ever reach and begin the emancipation as well as the discovery of unimaginable atrocities on the sites of concentration camps. Bogarde and Rampling had actually acted together before on The Damned which was released about five or so years prior to The Night Porter and similarly dealt with individuals dealing with the ramifications of their fascistic political entanglements. With the combination of their collective research and experience, the team was well prepared to make media concerning fascism and it’s effects while making a clear statement against it as a normative political ideology.

In a multitude of scenes intermixing film with theater, opera, music, and dance, Cavani works to theatricalize the seductive and controlling antics as fascism as a political ideology all confined within the parameters of flashback filmic memory and yet transmuted to the present by way of lasting desire. The extended passion of glances between the two lovers, Lucia and Max, is continued a second time with the setting of the Viennese opera. This is not, however, the only time the film cloaks the rekindling of fascist ideals with the aesthetics of theater. The first other significant theatrical episode comes earlier on in the film when Max meets one of his old covert Nazi friends at the hotel for what seems to be a semi-regular occurrence. The man performs a balletic dance while Max moves a spotlight for him. The scene quickly swells with louder music and flashes backward to him performing the same dance but in nothing but a small dance belt. In a parallel flashback, Lucia is seen in probably the film’s most iconic scene dancing and imitating Marlene Dietrich’s singing of a German standard while wearing elements of a male SS officer’s uniform. While she is bare chested, both Lucia as well as the male dancer are sexualized in these scenes. However, the male dancer is most certainly the more nude one and dances with a sort of pumped up desperation or enflamed desire. Lucia on the other hand languid, seductive, and powerful. Dressed as an officer, Lucia plays a different kind of role as she walks through the room. In way, she becomes just as real of a Nazi within the uniform as anyone even though she still remains a prisoner. Both performative sequences reiterate and reinforce the idea of the aesthetics of politics being on display as well as further examinations of desire and what it is to be implicated by the aesthetics of fascism. Interestingly, both sequences purposefully subvert expected gender and sexual conformity through wardrobe, framing, and music.

This swirling mix of lingering but pulsating memory and supercharged desire combine to synthesize a simulacrum of the dominance and control of fascism in the form of a sexual, abusive, and eventually codependent and ultimately doomed union. In the final quarter of the film, the two twisted lovers are essentially stand in’s for wartime prisoners from their collective past and Max’s once safe and quiet apartment has become a tiny prison that has already be enclosed upon and surrounded by Max’s old Nazi friends. One of the primary reasons that this film is so unconventional in the communication and signing of it’s messaging is the fact that the film does not rest on a binary sense of good and evil nor does it subscribe to a binary view or gender or even morality. Relationships such as Nazi and concentration camp prisoner that seem clear-cut and easy to decipher in the moment become complex and refracted as violence and sexuality converge within the narrative, exploding the sense of assigned sexual or gendered roles. As Max’s small flat becomes what seems to be the couple’s final resting place as hunger as well as Nazi agents begin to close in, the dynamics of this already ruinous relationship change even more. When she was essentially helpless when in the camp, this new situation allows Lucia both a position of victimhood and agency—she can choose whether or not to stay with Max or not. In choosing to stay, Lucia delves into sadistic exercises of her own including leaving glass for Max to step on as well as eating the sparse rations of food and leaving none for him Whereas explicit theatrical and operatic scenes and sets were staged previously to creatively display the seductive violence of nazism, it is Max’s apartment that is now the set stage. They are now the actors performing the barbarity of the Nazis crimes within the systemic and memory fueled abuse of their own relationship. The more they both give into the desire they have in the moment, the more the past is dug up and all at once is revived in the current time.

At the end of the film, the two lovers are finally shot to the ground dead by the nazis that had been hunting them all along. They lie motionless in the final frame, alone, cold, and utterly unknowable. In a film that brings the smoke and mirrors of fascist aesthetics out into clear sight, it’s final moments demonstrate that fascism’s ebbing heartbeat still continues due to secrecy and the implicit embedding of fascistic culture and ideology into the seams of capitalism that still ripple to this day. The Night Porter reminds us that fascist ideology lives on if precaution is not taken and often rears it’s head in the most surprisingly desirable and seductive way.

Bibliography

The Night Porter. Cavani, 1974. Film.

Ilsa, She Wolf of the SS. Edmonds, 1975. Film.

The Damned.Visconti, 1969. Film.

Marrone, Gaetana. The Night Porter: Power, Spectacle, and Desire. The Criterion Collection. DEC 9, 2014. Web.

Insdorf, Annette. The Night Porter. The Criterion Collection. JAN 10, 2000. Web.

Ravetto, Kriss. The Unmaking of Fascist Aesthetics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2001. Print.